Pergamon Altar – Discover the Famous Altar of Zeus

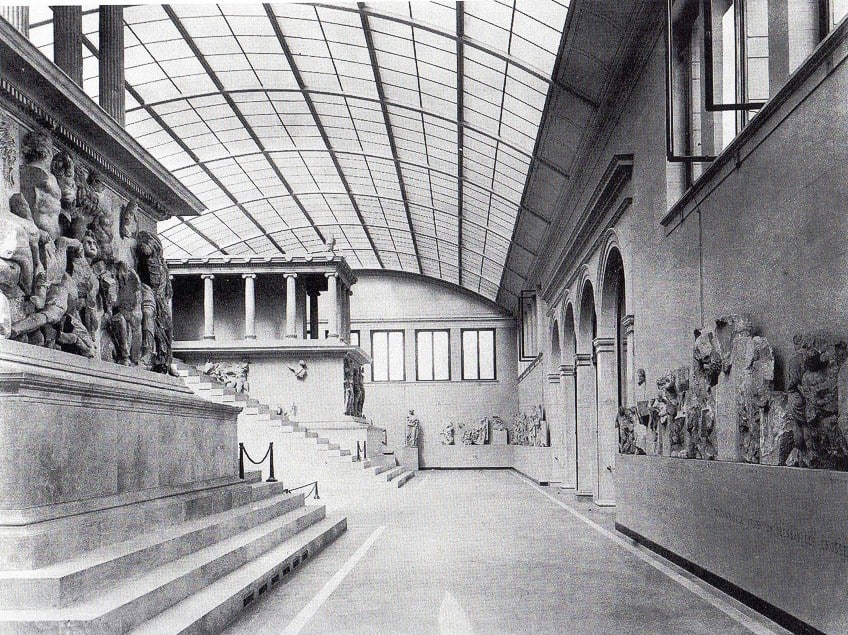

The mythical conflicts between the Olympian deities and the giants were depicted in a variety of mediums by ancient Greek artists, ranging from minute engraved jewels and vase paintings to larger-than-life-sized architectural sculptures. The Pergamon Altar is home to one of the most remarkable and well-preserved of these scenes. The Altar of Zeus was formerly situated in a holy precinct on the acropolis of Pergamon, which was governed by the Attalid dynasty from around 282 BCE. The Pergamon Altar was relocated to Berlin, Germany, in the early 20th century – almost 2,700 kilometers from its original location – and has remained on display as the museum’s centerpiece since 1930.

Table of Contents

Exploring the Pergamon Altar of Zeus

| Artist | Ancient Greek craftsmen |

| Date Completed | Early 2nd century BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (meters) | 110 x 36 x 34 |

| Location | Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany |

The Pergamon Altar was a colossal structure erected on one of the Pergamon’s acropolis terraces in Asia Minor under the reign of King Eumenes II in the first part of the 2nd century BCE. The base was adorned with a high-relief frieze depicting the Gigantomachy, the conflict between the Olympian deities and the fabled giants.

Another, less impressively preserved and smaller high-relief frieze surrounds the fire altar on the higher level of the construction at the top of the steps on the inner court walls.

The History and Significance of the Pergamon Altar

In the second part of the 20th century, several academics asserted that Eumenes II erected the altar in 184 BCE after defeating the Tolistoagian tribe and their commander Ortiagon. The altar’s architecture and friezes have resulted in the assumption that it was not intended as a monument to a specific triumph. The Gigantomachy fresco on the exterior walls of the altar makes no obvious references to war conflicts that occurred during that period. The Olympian deities’ conflict appears to instead have been a cosmological event with broad ethical implications.

The few vestiges of the dedicatory inscription also appear to imply that the altar was dedicated to the deities as a result of “favors” conferred upon them.

The divine recipients might be Zeus, the father of the Olympians, and his child Athena, who feature prominently on the Gigantomachy frieze. Bernard Andrea’s 2001 paper has one of the most recent proposals for dating the altar’s construction. Based on his research, the Altar of Zeus was built between 166 BCE and 156 BCE as a broad victory monument celebrating the Pergamenes’ victories over the Galatians, Seleucids, and Macedonians, and was believed to have been designed by Phyromachos. A ceramic fragment recovered in the altar’s foundation has been dated to around 172 BCE, signifying that the structure was built later.

Because significant sums of money had to be spent on fighting until 166 BCE, it is possible that the building of the altar could only begin until then.

Construction and Design

Previous iterations of the altar were flattened in Pergamon, and additional terraces were built to improve the acropolis’ function. The path linking the lower village to the acropolis passed straight through the self-contained and now expanded sacrificial altar area, which could be entered from the eastern side. Hence, guests in antiquity initially viewed the mural on the altar’s eastern face, which depicted the major Greek deities. Initially, Heracles, Hera, Zeus, Ares, and Athena were shown in combat on the northern side of the eastern frieze. Despite the height difference, the altar’s west side with the staircase was aligned with the Athena temple.

The Altar of Pergamon most likely emerged in direct correlation to the remodeling of the acropolis and was intended to be viewed as a significant, new structure and votive gift to the Olympians.

The Altar of Zeus was designed so that people could stroll around it in its open layout. This ultimately resulted in additional intended lines of sight. The altar was practically square in form. In this regard, it adhered to Ionic models, which called for a three-sided wall encircling the actual sacrifice altar. A staircase on the open side also leads to the altar. Such altars were often angled toward the east for ceremonial purposes so that individuals bringing offerings accessed the altar from the western side. For the inner courtyard, which housed the fire altar itself, a second columned hall was also envisioned but never built. A frieze representing the life of the city’s fabled founder, Telephus, was erected at eye level.

While no paint traces have been discovered, it has been assumed that the entire edifice was lavishly painted in antiquity.

Significance and Relation to Other Works

Contrary to the prevailing beliefs surrounding this monument, the Pergamon Altar was not a temple, but rather a temple altar, although altars were often positioned outdoors in front of their buildings. It is thought that the altar’s occult reference point was the Athena temple on the terrace of the acropolis above it and that the altar operated purely as a site of sacrifice. Many consecrating inscriptions and statue bases unearthed near the altar and whose benefactors mentioned Athena provide credibility to this argument. Another theory is that Athena and Zeus were both honored at the same time.

It’s also possible that the altar served a distinct function. Several older Greek art pieces served as models for a number of figures featured on the Gigantomachy frieze.

For instance, Apollo’s idealized position and fine features resemble a classical figure by the sculptor Leochares, created around 150 years before the Pergamon Altar frieze and already well-known in antiquity; a Roman replica has endured and is now housed in the Vatican Museum. The prominent group, which includes Athena and Zeus, traveling in opposing directions recalls the battle between Poseidon and Athena on the Parthenon’s western pediment. Such allusions are not by chance, given that Pergamon envisioned itself as a reincarnated Athens. The frieze, for its part, had an impact on subsequent works of antiquity. The most renowned example is the Laocoon Group, which was produced roughly 20 years after the Pergamon relief.

The craftsmen who made the statue group followed in the footsteps of the relief’s maker and may have even assisted in the creation of the frieze.

Controversies Surrounding the Pergamon Altar

Carl Humann, a German engineer, visited Pergamon for the first time in 1865. He was assigned to conduct geographic investigations and returned to the city several times over the next few years. He advocated for the conservation of the monuments on the Acropolis and sought to find collaborators to help with an excavation; however, as a private individual, he was not up to such a massive undertaking, lacking the necessary financial and logistical resources to do so. It was critical to start excavating operations as quickly as possible since Bergama residents were exploiting the altar as a quarry.

The German government obtained a permit to excavate in Turkey, and digging started in September 1878. By 1886, vast portions of the Acropolis had been studied and, in the years that followed, carefully evaluated and documented.

Beginning in 1879, the panels from the Pergamon Altar, together with some other pieces, were brought to Berlin and placed in the hands of the Collection of Antiquities under an arrangement between the German government and the Ottoman Empire. The Germans were all too well aware that by doing so, a work of art would be taken from its original site and that this would cause controversy. Many saw the removal of such a significant cultural item from Turkey as a breach of the country’s cultural heritage and a signal of imperialist intrusion.

Debate over Return

Istemihan Talay, Turkey’s Minister of Culture, sought the return of the Altar of Zeus and other antiquities in 1998 and once again in 2001. This demand, though, lacked official status and would not have been enforced under today’s criteria. With rare exceptions, the Berlin state museums, as well as other institutions in Europe and the United States, generally rule out the prospective repatriation of historic pieces of art. German museums’ policy of not surrendering cultural artifacts seized from other countries has sparked international condemnation and controversy.

Although some people in Germany claim that returning these antiquities would create a precedent for the return of artifacts in other nations’ collections, others contend that the practice is out of date and ignores the colonial past of cultural exploitation.

Numerous countries, notably those from whom the artifacts were taken, have voiced a longing for their return. For instance, Greece has long desired the repatriation of the Elgin Marbles, which were stolen from the Parthenon by British ambassador Lord Elgin and are currently kept in the British Museum. Likewise, Egypt has demanded the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone, which is housed in the British Museum. The subject of whether cultural relics should be repatriated to their nations of origin is a complicated and challenging one, with vastly differing perspectives. While some say that institutions have a responsibility to conserve and disseminate cultural heritage, others think that the repatriation of artifacts is required to redress historical injustices and guarantee that cultural heritage is available to the communities from whom it originated.

The majority of the altar foundation, as well as many wall fragments, remain in their original place today. Many minor fragments of the frieze were discovered subsequently in Turkey.

Restoration Work on the Pergamon Altar

The Pergamon Altar needed to be restored since it is almost 2,000 years old and has deteriorated over the ages, as well as degradation from certain environmental factors and human activities. This has resulted in material loss, cracks, and structural instability, which needed to be rectified to prevent additional damage and assure the Altar of Zeus’ long-term preservation. The altar is an incredibly valuable and significant cultural relic, both historically and artistically.

Challenges

It is one of the most significant instances of ancient Greek sculpture, which means that it is an essential part of humanity’s cultural legacy. As a result, ensuring its preservation was seen as critical. The Pergamon Altar is a vast and intricate monument with exquisite reliefs and a brittle framework, which made the restoration work difficult. This created challenges in accessing and working on certain parts, and it necessitated a substantial amount of expertise and caution to assure that the restoration work would not potentially cause more harm.

The Pergamon Museum in Berlin, which houses the altar, is a problematic setting for the preservation of antique objects.

The museum is vulnerable to humidity and temperature variations, as well as air pollution, all of which might contribute to the degradation of the monument. To assure the monument’s long-term preservation, the restoration effort had taken these environmental conditions into account as well. The Pergamon Altar renovation was an enormous and demanding effort that took a great time and financial investment. It required a team of archaeological, conservational, and restoration professionals, as well as innovative technologies and materials.

A number of financial and support sources, including the German government and individual benefactors, were also necessary for the restoration project to take place.

Restoration Work

The Pergamon Museum in Berlin launched a substantial restoration effort on the altar in 2014. The restoration effort aimed to retain the altar’s historical value while simultaneously addressing concerns of stability and conservation. A team of conservation, archaeology, and restoration professionals worked together to painstakingly repair the monument using a variety of old techniques and modern technologies. One of the primary goals of the restoration effort was to strengthen the altar’s structure, which had deteriorated over time owing to its age and the museum’s climatic conditions.

To address this problem, the renovation team employed a multitude of methods, involving stainless steel rod reinforcing, crack and void filling using a specifically designed mortar, and the implementation of a sophisticated climate control system to manage the museum’s humidity and temperature levels.

The complex reliefs on the altar were also cleaned and conserved as part of the restoration effort. This was accomplished with the use of a combination of classic cleaning methods and contemporary technologies, such as 3D imaging and laser scanning, which assisted in identifying areas of damage and guiding the restoration process. The repair of the Pergamon Altar was a complicated and difficult job that demanded a high degree of knowledge and coordination across several disciplines.

The ensuing restoration has served to maintain the artistic value of this significant cultural monument, guaranteeing that future generations can keep learning about and appreciating it.

The Pergamon Altar Today

The Pergamon Altar is presently on exhibit at Berlin’s Pergamon Museum. The altar was restored to its former location in the museum’s grand hall after the restoration work concluded in 2019, and can now once again be enjoyed by visitors.

The restoration effort has assisted in stabilizing the altar’s structure and resolving preservation and conservation concerns.

As a result, the altar is again in excellent condition and will be able to survive the strains of display for many more years to come. Guests to the Pergamon Museum can take a close look at the Pergamon Altar and learn about its exquisite features and rich history. The monument is shown with other Greek and Roman antiques, as well as other significant cultural items from throughout the world.

This massive Altar of Zeus is a masterwork of Greek Hellenistic art. The Pergamon Altar, as with the Parthenon in Athens, is built on an acropolis terrace that overlooks the historic city of Pergamon. However, it was not a temple, like the Parthenon, but rather an altar built in the Ionic order of Greek architecture. The Gigantomachy frieze is a remarkable example of Hellenistic sculpture overflowing with action, passion, and motion, with over 100 panels depicting gods in conflict with giants. Thanks to extensive restoration works in the 21st century, this magnificent monument will still be around for us to enjoy for many years to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Story Is Depicted on the Pergamon Altar’s Frieze?

The fabled conflict between Mount Olympus’ deities and the giants, who were the descendants of the earth goddess Gaia, is shown in the Gigantomachy frieze on the Pergamon Altar. The giants were a strong and dangerous race who arose against the gods in an effort to topple them and seize control of the cosmos, based on Greek mythology. The gods are portrayed on the frieze riding chariots and battling with spears, swords, and other weapons, while the giants are portrayed as violent, grotesque monsters with wild hair and animal-like characteristics. The battle is seen taking place on Mount Olympus and in the surrounding terrain, with both sides using boulders and branches as weapons.

Why Is the Current Location of the Altar of Zeus Controversial?

The Pergamon Altar was relocated to Berlin in Germany after it was rediscovered by a German man by the name of Carl Humann in 1865. The German government made a deal with the rulers of that time, the Ottoman Empire, to take it back to Germany for preservation. However, recently, the government of Turkey has called for the return of the monument to its country of origin.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Pergamon Altar – Discover the Famous Altar of Zeus.” Art in Context. July 5, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/pergamon-altar/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 5 July). Pergamon Altar – Discover the Famous Altar of Zeus. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pergamon-altar/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Pergamon Altar – Discover the Famous Altar of Zeus.” Art in Context, July 5, 2023. https://artincontext.org/pergamon-altar/.