Duomo di Milano – The Milan Cathedral Architecture

The Duomo di Milano Cathedral (or Milano Duomo) is known to the English-speaking world as the Milan Cathedral. The Duomo Milano Cathedral is the seat of the Archbishop of the city and is dedicated to the Nativity of St. Mary. Today, we will be taking a look at the history and construction of the Milan Cathedral’s interior and exterior, and answer your questions about the Milano Duomo, including, “When was Duomo di Milano built,” “who built the Duomo di Milano”, and “where is Duomo di Milano located?”.

The History of the Duomo di Milano Cathedral

| Architect | Simone da Orsenigo (c. 14th century) |

| Period of Construction | 1386 – 1985 |

| Function | Seat of the Archbishop of Milan |

| Height (meters) | 108 |

| Location | Via Carlo Maria Martini, Milan, Italy |

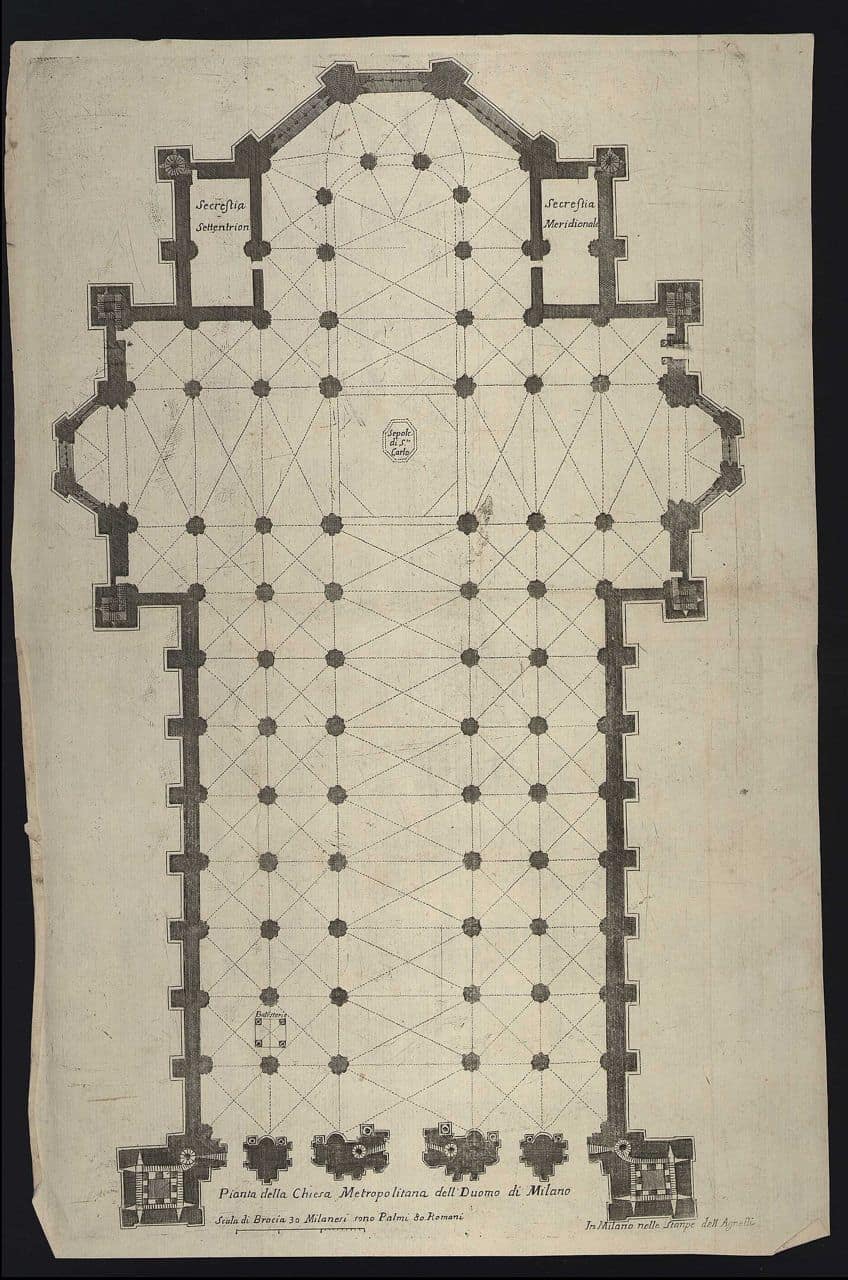

It would take almost 600 years for the construction to be completed, which required many Milan Cathedral architects, engineers, and builders throughout the years. The Duomo di Milano Cathedral is officially the largest cathedral in Italy as the bigger St. Peter’s Basilica is located in the sovereign state of Vatican City (which is not considered a part of the Italian Republic). Today it is still evident what an important role the Milano Duomo played in its time as the layout of the city reveals that all the roads radiate outward from (or circle) the centrally located cathedral.

It seems to have been an important site even before the Duomo di Milano was constructed, as remains of an even older church built in 355 CE have been excavated from underneath the cathedral. Around 20 years later, in 335 CE, an octagonal baptistery was built that can still be accessed by visitors today. This original cathedral was razed in a fire in 1075 and would be rebuilt around 300 years later as the Milano Duomo.

Initial Construction of the Duomo di Milano Cathedral

Archbishop Antonio da Saluzzo initiated the cathedral’s construction in 1386. Gian Galeazzo Visconti, cousin of the Archbishop had ascended to power after the fall of the tyrannical Barnabò, and the cathedral was built as a reward for the working and noble classes who had all suffered terribly under his rule. The decision to construct the building in central Milan was based on certain political agendas: the people of Milan had hoped to prove to the new ruler that the location was central and powerful, in response to his decision to rule from Pavia instead of Milan. Three remaining structures first had to be demolished before work on the new cathedral commenced: the Baptistry of St. Stephen, The Ordinari Palace, and the Archbishop’s former palace.

The old St. Maria Maggiore church was used for quarrying stones. Shortly after construction began, the Milanese population began to grow excited as news spread about the new cathedral, and Visconti and his cousin took advantage of their enthusiasm by collecting large public donations for the construction. An organization known as the Fabbrica del Duomo was created to oversee and regulate the 300 people needed to construct the cathedral, who would be supervised by Simone da Orsenigo, the project’s first chief engineer. His initial plan was to build the Milano Duomo in the Lombard Gothic style from brick. For Visconti, it was essential that the newest European architectural trends be followed.

Nicolas de Bonaventure was appointed as the chief engineer in 1389 and began to incorporate the Rayonnant Gothic style.

The Fabbrica del Duomo was provided with exclusive access to the Candoglia quarry’s marble supply and it was also exempted from having to pay any taxes. In around 1399, Jean Mignot, an architect from France, was brought from Paris to assess the work and make improvements where necessary to accommodate the stones that would be hoisted to higher altitudes than ever before. Upon inspection of the work, he stated that it had not been built using any technical science and was in jeopardy of falling into ruin. Despite never crumbling as the Frenchman had anticipated, the analysis still prompted the engineers to improve their techniques and tools.

There were regularly tense moments between the Visconti and the factory’s top management, who had been chosen by the Milanese citizens. He had wanted to turn the building into the mausoleum of the Visconti, planning to add the funerary monument of his father, the former Visconti, Galeazzo II. However, the citizens as well as the factory did not want the cathedral only associated with the ruling class, underlining their autonomy. This led to a clash that resulted in the establishment of the Certosa di Pavia, which would be used exclusively as the site for the Visconti dynasty.

When Galeazzo passed away in 1402, the construction of the cathedral had already reached the halfway mark. Yet, construction almost completely came to a halt after that until 1480 due to the lack of funds and ideas. The few parts that were constructed during this period, however, include the tombs of Pope Martin and Marco Carelli in 1424, as well as the incorporation of the windows of the apse in the 1470s. The aisles and nave were also constructed up to the 6th bay by Francesco Sforza in 1452.

Both Donato Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci submitted models for a design competition for the cathedral’s central cupola in 1488, however, Da Vinci subsequently withdrew his submission. In the Milan Cathedral’s interior, from 1500 to 1510, the cupola was added and decorated with 60 statues of various sibyls, prophets, saints, and biblical figures. Excluding a spire that was constructed between 1507 and 1510, there was little progress on the building’s exterior during this period. While the Milan Cathedral’s interior remained largely incomplete, it was still considered to be usable during the period of Spanish domination.

A large organ was commissioned to be built by Giacomo Antegnati in 1552 for the choir’s northern side.

Continued Construction Under Borromeo

All of the monuments in the cathedral, including the tombs of Filippo Maria Visconti, Giovanni, and many more were all removed following the appointment of Carlo Borromeo as the new Archbishop. Yet, his most contentious move was to appoint Pellegrino Pellegrini as the project’s chief engineer in 1571, as he was not one of the duomo’s lay brothers, and his appointment would necessitate revising the statutes of the Fabbrica del Duomo. As the Gothic style had grown to be seen as foreign, Pellegrini and Borromeo sought a new Renaissance aesthetic for the Duomo to emphasize its Italian and Roman heritage. Pellegrini, therefore, designed a facade with obelisks and columns to give it a distinctly “Roman” appearance. It was never implemented though.

Construction in the 17th Century

Federico Borromeo had the foundations of the new facade constructed by Fabio Mangone and Francesco Maria Richini at the start of the 17th century. Construction continued up until 1638 with the inclusion of two windows and five portals. However, in 1649, Carlo Buzzi, the new chief architect, implemented a dramatic change: the facade was to be restored to its former Gothic appearance, with the already completed elements inside large Gothic pillars and two huge belfries. Other designs were submitted, including those by Luigi Vanvitelli and Filippo Juvarra, but none were used.

The facade of Santa Maria Maggiore was dismantled in 1682, and the cathedral’s roof was finished.

The Madonnina’s spire, one of the cathedral’s major highlights, was built in 1762 at a breathtaking height of 108 meters. Carlo Pellicani built the spire, which features a famous polychrome Madonnina sculpture created by Giuseppe Perego and suits the cathedral’s grandeur. Given Milan’s typically wet and foggy environment, the Milanese consider it a good day when the Madonnina can be seen from a distance, as it is usually obscured by mist.

Completion of Construction

Napoleon Bonaparte, who was about to be declared King of Italy, ordered Pellicani to complete the facade on the 20th of May, 1805. In his eagerness, he informed Fabbrica that all expenditures would be covered by the French treasury, which would compensate Fabbrica for the real estate that had to be sold. Even though this compensation was never received in the end, it meant that the cathedral’s facade was finished in only seven years. Pellicani mostly copied Buzzi’s design, adding neo-Gothic elements to the top windows. As a gesture of gratitude, a monument of Napoleon was erected on one of the spires, and he was later crowned King of Italy at the Milano Duomo. The majority of the missing spires and arches were built in the years that followed. From 1829 until 1858, new stained glass windows replaced the previous ones, although the results were less visually pleasing.

The cathedral’s final elements were completed only in the 20th century, with the last portal completed on the 6th of January, 1965. This date is regarded as the end of a process that had been going on for centuries, however, some uncarved blocks remain to be finished as sculptures to this very day. Allied bombardment of Milan during WWII further slowed development. The Duomo, like many other cathedrals in towns bombarded by Allied troops, sustained some damage, but to a smaller degree than other prominent structures in the vicinity. It was rapidly restored and converted into a haven for displaced locals. In November 2012, authorities started a drive to raise funds for the duomo’s restoration by inviting people to “adopt” the building’s spires.

The impact of urban pollution on the 14th-century edifice necessitated annual maintenance, and subsequent cuts to Italy’s cultural budget left less money for the care of cultural sites, including the Duomo di Milano.

There were many Milan Cathedral architects over the centuries resulting in the incorporation of many styles – some contrasting in aesthetic. Therefore, the public reaction to its design has ranged from disgust to admiration. One critic wrote that while the cathedral managed to steal from every architectural style found around the world, it somehow also managed to spoil them all. It is a blend of both Flamboyant Gothic and Perpendicular Gothic. Oscar Wilde visited the cathedral in 1875 and wrote that it was an “awful failure with inartistic and monstrous designs”, in a letter to his mother back home. Yet, not all criticisms were harsh, with some referring to his as “solemn, grand, delicate, and graceful”.

It took almost 600 years for the Duomo di Milano Cathedral to be built! This accounts for the endless list of architects who were all involved in the Milano Duomo’s construction. It also accounts for the sometimes contradictory architectural styles that were incorporated into the cathedral’s design. Its construction was also halted on several occasions due to various political shifts in power, as well as modified to accommodate and reflect those changes. Yet, despite the long period of construction, it was eventually (mostly) completed by 1985.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was Duomo di Milano Built?

Initial work on the cathedral began in 1386. However, the first step was to demolish older buildings on the site, which means that there had been some kind of church there since sometime in the 300s CE! Construction would continue on and off for the following six centuries.

Who Built the Duomo di Milano?

In order to facilitate and oversee the construction of the cathedral, an organization called the Fabbrica del Duomo was formed. It constituted around 300 people, including the various designers, engineers, laborers, and everyone else needed to construct the Duomo di Milano Cathedral. The Fabbrica del Duomo was afforded certain exclusive rights, such as their access to marble quarries, and they were also exempt from having to pay taxes. However, things were not always smooth between the Fabbrica del Duomo and the Visconti, as they did not want the building to be used to house the monuments and tombs of the nobility as he had wanted.

Where Is Duomo di Milano Located?

The designers wanted the cathedral to be placed in a very central part of Milan. This served to secure its position as a powerful location from which to conduct certain affairs. The significance of its location can be observed in the way that all the streets seem to radiate outward from it, as well as circle it.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Duomo di Milano – The Milan Cathedral Architecture.” Art in Context. June 27, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/duomo-di-milano/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 27 June). Duomo di Milano – The Milan Cathedral Architecture. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/duomo-di-milano/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Duomo di Milano – The Milan Cathedral Architecture.” Art in Context, June 27, 2023. https://artincontext.org/duomo-di-milano/.