Walker Evans – Father of American Documentary Photography

Walker Evans’ photography presented the tale of working-class life in America with an uncompromising candor that was genuinely innovative for the time. Walker Evans’ art went further than other artists in its reluctance to glamorize destitution, drawing heavily on the American cultural heritage. The candid attitude to portraiture and documentation in Walker Evans’ polaroids altered both genres for future generations and changed how society perceives itself. Walker Evans’ photographs are largely regarded as some of the greatest photographic works of that era.

Table of Contents

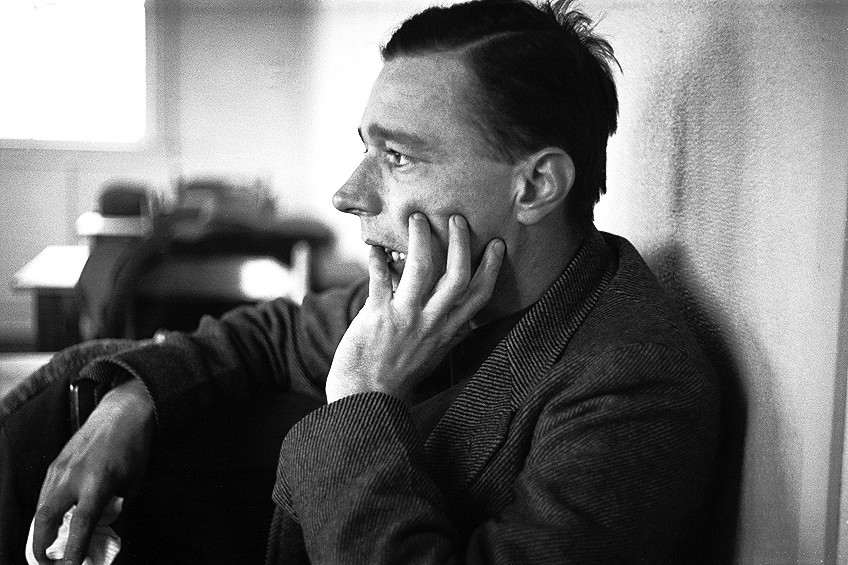

The Art and Life of Walker Evans

| Nationality | American |

| Date of Birth | 3 November 1903 |

| Date of Death | 10 April 1975 |

| Place of Birth | St. Louis, Missouri |

Ernest Hemingway, a wonderful representation of the relationship connecting literature and art in the 20th century, influenced Evans’ early approach. In Cuba, the pair became drinking companions, and the stark simplicity of Evans’ pictures is influenced by Hemingway’s brief, straightforward style. Evans was relatively small and delicate, which enabled him to capture shots before anyone saw him.

He was also a technological whiz, having been among the first to employ progressively mobile cameras and shorter exposure periods. His perceptions of working-class society were formed by visual, artistic, and literary influences. The illustrators of New York street life, from Edward Hopper to George Bellows, were some of his most influential of these sources.

Early Period

Evans, who was born into a wealthy family in St. Louis, began taking photos as a youngster and proceeded to do so after the family relocated to Chicago and then Ohio. Evans arrived in New York after a brief spell at Williams College, where he hoped to become a poet and author. Among his personal idols were D. H. Lawrence, T.S. Eliot, and E.E. Cummings. However, while in New York, he suffered from debilitating writer’s block. He “felt compelled to write so badly” that he “couldn’t compose a single sentence.”

Evans, unable to create and in need of a job, accepted low-paying jobs at the New York Public Library and many bookstores, where he was free to travel and read. Following several years of dead-end work and little luck in the publishing business, the young man packed his possessions and set sail for Paris, still intending to pursue his creative dreams. Writing prose was more difficult for Evans in Paris, but it was a moment of immense “intellectual excitement,” according to the artist.

Evans was inspired to follow Eugene Atget’s and his student Berenice Abbott’s tour around Paris after viewing their work (two other early 20th century greats to whom Evans was greatly attached).

In 1927, he moved to New York and became a member of an emerging literary community that was becoming increasingly entwined with art. Its members included Hart Crane, John Cheever, and Lincoln Kirstein. Evans’ fledgling interest in photography was sparked by this network and quickly developed into full-fledged love.

By 1929, he was shooting ambitious images of the city’s buildings and machinery, and he had reverted to his interest in Atget’s works, whose austere photographs of Paris echoed his developing distaste for artistic gimmickry. Evans was inspired and decided to explore more into photography, eventually publishing his work and earning contracts for picture series.

On one such contract, the artist was dispatched to Cuba in 1933 to work on Carleton Beals’ book The Crime of Cuba (1933). During this project, Evans befriended and drank regularly with Ernest Hemingway, who assisted the artist in extending his time in Havana by a week.

Evans’ images of Cuban coastal life on the streets, homeless, and police officers mark the start of his departure from the formality of modernism and toward his own particular style of realism. Before departing Havana, Evans handed 46 photographic prints to his drinking partner, who soon forgot them, concerned that some of his images might be labeled subversive and consequently confiscated by the Cuban government.

In 2002, these images were recovered and displayed.

Mature Period

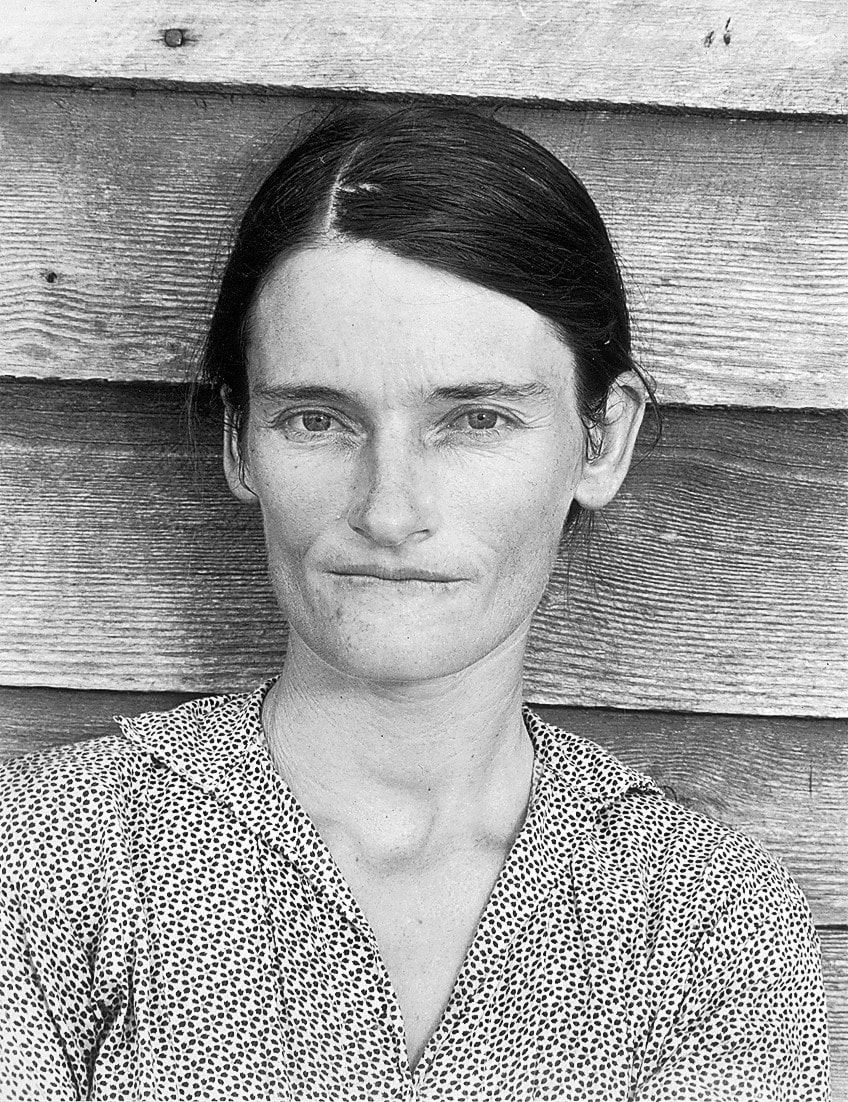

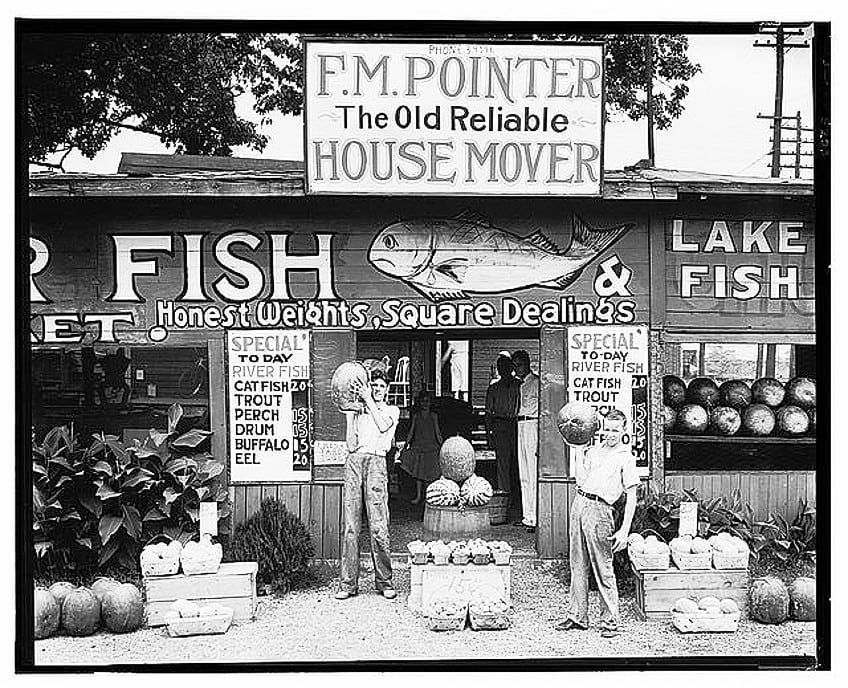

During the Great Depression, photography blossomed because of Roosevelt’s New Deal, which paid artists to work. The FSA recruited Evans and other photographers to capture the government’s attempts to rehabilitate rural towns. Evans spent a good portion of 1935 and 1936 beautifully depicting the visual texture of everyday life through rural churches, bedrooms, fading signs, and raggedy work clothing, uninterested in the political theory underpinning his task.

He avoided utilizing high-end equipment. Despite his familiarity with and ability to acquire cutting-edge technology, Evans employed an obsolete camera with a very slow lens, exactly as his idol, Eugène Atget, had done in Paris.

In 1936, he partnered with writer James Agee on an editorial for Fortune magazine that included images and prose on tenant farmers. Fortune never released the images that resulted from this assignment, but Evans and Agee’s work was compiled into a book called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in 1941, a sequence of pictures that unwaveringly conveys the raw misery of the Great Depression.

Evans’ skill for portraying the American vernacular was acknowledged by the Museum of Modern Art with his first solo show in 1938. Evans started shooting a collection of clandestine photographs aboard the New York City subway about the same time. These images, like his previous work, depicted unassuming moments in ordinary life with clear exactness. He encountered and wedded Isabelle Storey in 1958. It was a dissatisfying relationship that ended in separation a little more than 10 years later. Evans was a really quiet individual who kept to himself.

In his personal life, he gravitated toward authors rather than artists as companions. In 2008, his ex-wife, Storey, released a fascinating autobiography in which she described her late husband as a quirky, driven, funny, but frequently caustic individual who could be a self-absorbed elitist. Despite his tolerance with the camera and affection for working-class heroes, Evans was clearly short-tempered and susceptible to unprompted wrath in the posh circles in which he and his wife moved.

Evans joined the Yale University School of Art as a lecturer in 1965. From then on, he worked on a few photographic projects. While his output as an artist was less prolific, he continued to teach until his passing in 1975.

The Legacy

Evans’ tremendous influence on the area of photography is undeniable. While he despised flashy equipment and too aesthetic photographs, Evans was one of the first documentary-style photographers to exhibit his work in the setting of gorgeously bound and expensively made volumes. This provided a consistent mechanism for creative expression, allowing his images to be viewed as art and laying the framework for succeeding photojournalists to present their works as art as well.

Evans, a dedicated teacher as well as a photographer, influenced a plethora of artists, including photographers Robert Frank, Helen Levitt, Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, and Hilla Becher.

Sherrie Levine, a postmodern photographer, went so far as to re-photograph Evans’ Depression-era photographs for a series named After Walker Evans (1981). Although some have seen Levine’s artwork as a critique of Evans, Levine himself stated: “I wanted to create images that opposed each other. I wanted to layer one image on top of another such that at times both images vanished and at other times they were both visible. For me, the work was really about that resonance – that place in the middle where there is no picture, but an emptiness, oblivion.”

Evans’ influence on current photography is undeniable. Artists tend to allude to his images, which sum up historical moments and our culture’s interpretations of those moments, whether in critique or adoration.

Walker Evans’ Photography

There were two conflicting photographic ideologies during Evans’ time: documentary-style versus pictorialist style. Documentary aimed to depict the world as it was, warts and all; pictorialism, on the other hand, offered a selected, transcendent picture of the world, comparable to classic Western artwork.

Walker Evans’ artwork, a synthesis of these two ideologies, added subtlety to the discipline of photography.

“What I feel is very wonderful in the so-called documentary style to photography, in my opinion, is the addition of poetry made unknowingly, even unwittingly and accidentally by the photographer,” he says. Walker Evans’ photographs depict a tremendous class-based quandary. Evans, who grew up in a wealthy home, never truly connected with the poor country farmers he represented.

Walker Evans’ polaroids, in addition to immediate observation, largely depended on literary sources for his observations, producing a type of closed system that reaffirmed an outsider’s view.

Citizen in Downtown Havana, Cuba (1933)

| Date Completed | 1933 |

| Medium | Gelatin Silver Print |

| Dimensions | 22 cm x 11 cm |

| Current Location | Walker Evans Archive |

Evans came to Havana in 1933 to photograph for Carlton Beals’ The Crime of Cuba (1933), a book that condemned dictator Gerardo Machado’s corruption. His bosses urged him to capture emotionally charged photos to accompany Beals’ eloquent words. Evans rejected their advice and crafted inconspicuous perspectives that imply upheaval.

In this photograph, Evans captures a tall guy in a white suit turning, possibly aware that he is being observed.

His hat tilt and sidelong gaze make him appear intriguing as if he were a figure from one of the period’s famous murder mysteries for cinema or television. Instead of gazing up and out, he avoids establishing visual contact with the lens or the individual who holds it.

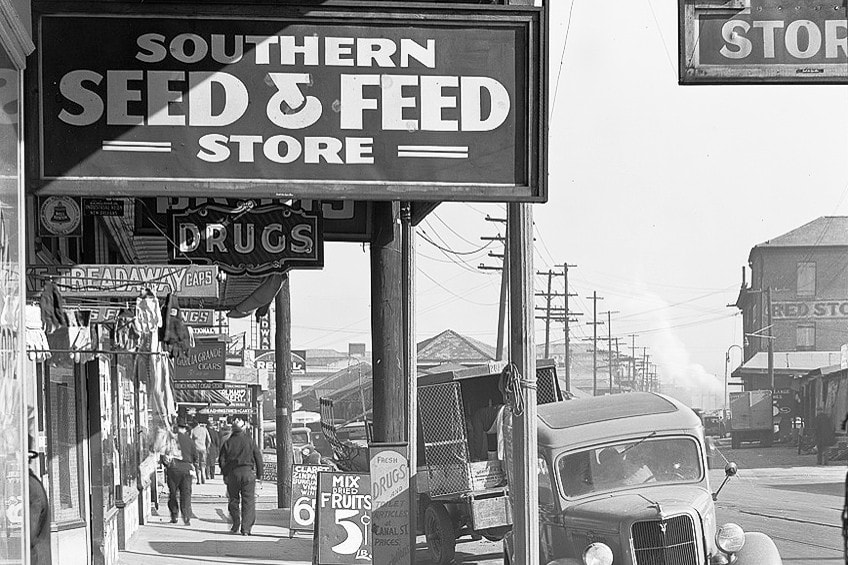

Roadside Stand Near Birmingham, Alabama (1936)

| Date Completed | 1936 |

| Medium | Gelatin Silver Print |

| Dimensions | 20 cm x 25 cm |

| Current Location | Office of War Information Photograph Collection |

The strength of Walker Evans’ photography lies in the fact that he so features the effect of conditions on acquainted organisms that the single house, or even the single faces, attacks with the power of vast numbers, the truly awful combined total pressure of multitudes of faces, residences, and roads.

Evans, wary of producing art that may be used as government propaganda, said (possibly defiantly) when he began this venture: “This is a true record, not a piece of propaganda. There will be no politics at all.” Evans’ aesthetic philosophy, as much as his images, was characterized by a steadfast refusal to be influenced by political dogma.

Subway Portrait (1941)

| Date Completed | 1941 |

| Medium | Gelatin Silver Print |

| Dimensions | 20 cm x 25 cm |

| Current Location | Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Evans photographed dozens of people who were engrossed in discussion, reading, or lost in concentration. Their attitudes and reactions, unaware of the camera, embody the subway’s unwritten rule for human conduct, a blend of secrecy and familiarity.

They also highlight persons’ characteristics.

A well-dressed man leans forward, impatiently, and focuses his gaze on an advertisement or a sign above him. Another commuter’s hand is gripping the newspaper to his right. The stiffness in their positions is necessary for keeping balance on the train, but it also portrays the metropolitan environment’s continual stress.

Recommended Reading

Today we covered the life and art of Walker Evans. Walker Evans’ polaroids managed to combine several types of photography into his own unique vision of the world around him. If you would like to read more about Walker Evans’ photographs and lifetime, then check out these awesome books.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Families (2001) by James Agee and Walker Evans

In 1936, writers James Agee and Walker Evans traveled to the South to work for Fortune magazine and document the everyday lives of sharecroppers. Their quest would prove to be an exceptional collaboration—as well as a literary watershed moment. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was met with widespread appreciation.

- Published to enormous critical acclaim

- Unsparing record in words and pictures of the South

- With an additional sixty-four archival photos in this edition

Many Are Called (2004) by Walker Evans

This book took a long time to come to fruition. Walker Evans began secretly photographing individuals on the New York City subway in 1938. He photographed the faces of motorcyclists rushing through the dark tunnels, immersed in their own private thoughts, with his camera hidden in his coat, the lens peering through a buttonhole. This magnificent new edition, released in the centennial year of the New York City subway, is a must-have for all fans of Evans’ exceptional images.

- Beautiful new edition of this work

- For lovers of the great City of New York

- Essential book for all admirers of Evans’s unparalleled photographs

Walker Evans is considered by many people to be one of the 20th century’s most significant photographers. His exquisite, crystal-clear pictures and lucid publications have influenced multiple generations of artists. Evans, the father of documentary-style photography in America, had the amazing capacity to view the moment as if it were already the past and to transfer that information and culturally flavored vision into a lasting art form.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Walker Evans?

Walker Evans was a well-known American photographer best recognized for his black-and-white photographs depicting the effects of the Great Depression. Evans, as an artist, despised formal photography. Instead, he sought to depict the mundane beauty and diaristic happenings of everyday life.

Why Was Walker Evans’ Photography Important?

Critics are still divided on whether his images foster empathy or perpetuate isolation from the people, whose circumstances were so dissimilar to his own. Evans’ clinical accuracy has been regarded as frigid and unfeeling. In his defense, Evans recognized these class-based antagonisms years before others did. Attempts to address it abound in his quotations.

Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Walker Evans – Father of American Documentary Photography.” Art in Context. April 8, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/walker-evans/

Anthony, J. (2022, 8 April). Walker Evans – Father of American Documentary Photography. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/walker-evans/

Anthony, Jordan. “Walker Evans – Father of American Documentary Photography.” Art in Context, April 8, 2022. https://artincontext.org/walker-evans/.