How To Write a Poem – A Detailed Guide to Writing Poetry

Poetry has a way of making sense of human emotion in a way that is both enthralling and baffling, turning sorrow and melancholy into something beautiful, and joy into something that almost leaps off the page. For every person, there is at least one poem that has touched and lingered in their hearts. What is yours? There is a wonderful quote from the film, The Dead Poets Society (1989) by the character John Keating, “We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race […] And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.” What about you, would you like to try your hand at poetry writing but don’t know how to write a poem? Below we have provided a guide on writing poetry for beginners, where you will learn how to write poetry in no time.

Table of Contents

- 1 What Makes a Piece of Writing a Poem?

- 2 Why Do People Write Poetry?

- 3 Elements of Poetry

- 4 How To Write a Poem: Step-by-Step

- 4.1 Step 1: Think of a Topic – What Is Your Poem About?

- 4.2 Step 2: Write Down Your Ideas – Generating Material

- 4.3 Step 3: Choose a Form for Your Poem

- 4.4 Step 4: Do Research – Read Poetry

- 4.5 Step 5: Write the First Draft

- 4.6 Step 6: Read Your Poem Out Loud

- 4.7 Step 7: Take a Break

- 4.8 Step 8: Revise Your Poem

- 5 Frequently Asked Questions

What Makes a Piece of Writing a Poem?

A poem is by definition one piece of poetry. When we think of a poem, we might think of a grouping of words or sentences that rhyme. However, poems do not have to rhyme, nor do they use any specific vocabulary or format. What makes a poem a poem is that it does present words in an artistic way by using figurative language. Form and rhythm is important in a poem. Prose, however, would write sentences and paragraphs without metrical structure but in a structure that represents the natural flow of speech.

Why Do People Write Poetry?

People write poetry for all sorts of reasons. The purpose of poetry is not only to express emotions and ideas but to also tell stories, convey messages and even teach lessons. When writing a poem, it helps to keep the goal in mind – Are you writing a poem for a school project? Is it to express your feelings to someone special? Or perhaps it is for a poetry reading evening at a local club.

Whatever the reason, the intention behind the poem will help you write it.

Elements of Poetry

A number of key ingredients are used to bake the cake that is poetry and distinguishes a poem from other types of writing, like a novel or a speech. These, which we will discuss below, are form, rhyme, rhythm, and sound. What poetry does use, however, that is similar to other creative writing is figurative language and allegories to convey themes to the reader. There is also free-verse poetry which has become quite popular since the 20th century, and these poems do not need to stick to a specific length, need a meter or rhyme scheme.

Sound in Poetry

One can often make out that a poem is a poem when it is read aloud. You can make a poem quite impactful through the words you use to highlight images and emphasize significant phrases. By using sound, you can make a poem pleasing or disturbing, setting the tone for the atmosphere of the poem. Sound can be created by using various literary devices. These are consonance, assonance, and alliteration to name a few.

Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849) used assonance in his poem, The Bells (1848) by implementing the letter “e” to convey the sound of a ringing bell.

“Hear the mellow wedding bells,

Golden bells!

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells!”

Rhythm in Poetry

There is rhythm in poetry, a beat, and pace, which is why songwriting is basically poetry made to music. A poem’s meter is its rhythmic structure and refers to the combination of both stressed syllables and unstressed syllables, and how many there are in each line. What is meant by “stressed” syllables is that certain sounds are emphasized when saying a word. This pattern is important to some traditional forms of poetry. A unit for poetic meter is known as a foot, and the most used metrical feet are trochaic, anapestic, iambic, spondaic, and dactylic. The number of feet used in a line determines its meter. The different types of poetic meter are:

- Monometer, which is one foot per line.

- Dimeter, consisting of two feet per line.

- Trimeter, consisting of three feet per line.

- Tetrameter, which is four feet per line.

- Pentameter, which has five feet per line.

- Hexameter, consisting of six feet per line.

- Heptameter, which has seven feet per line.

- Octameter, which has a whopping number of eight feet per line.

All this talk of poetic meter and feet to create rhythm in poetry may seem a bit confusing, so we have given explanations below of a few metrical feet commonly used in poetry as well as examples to help better understand how they work.

Iamb

This metrical foot also consists of two syllables but is opposite to the Trochee. The first syllable is unaccented while the second syllable is. For example, the word beseech, with the accented syllable being underlined. The following example is from the poem, Alone (1829) by Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849). The emphasized syllables are underlined.

Each line in the passage has four iambs and is therefore an iambic tetrameter.

“From child hood’s hour I have not been

As others were— I have not seen

As others saw— I could not bring

My passions from a common spring—”

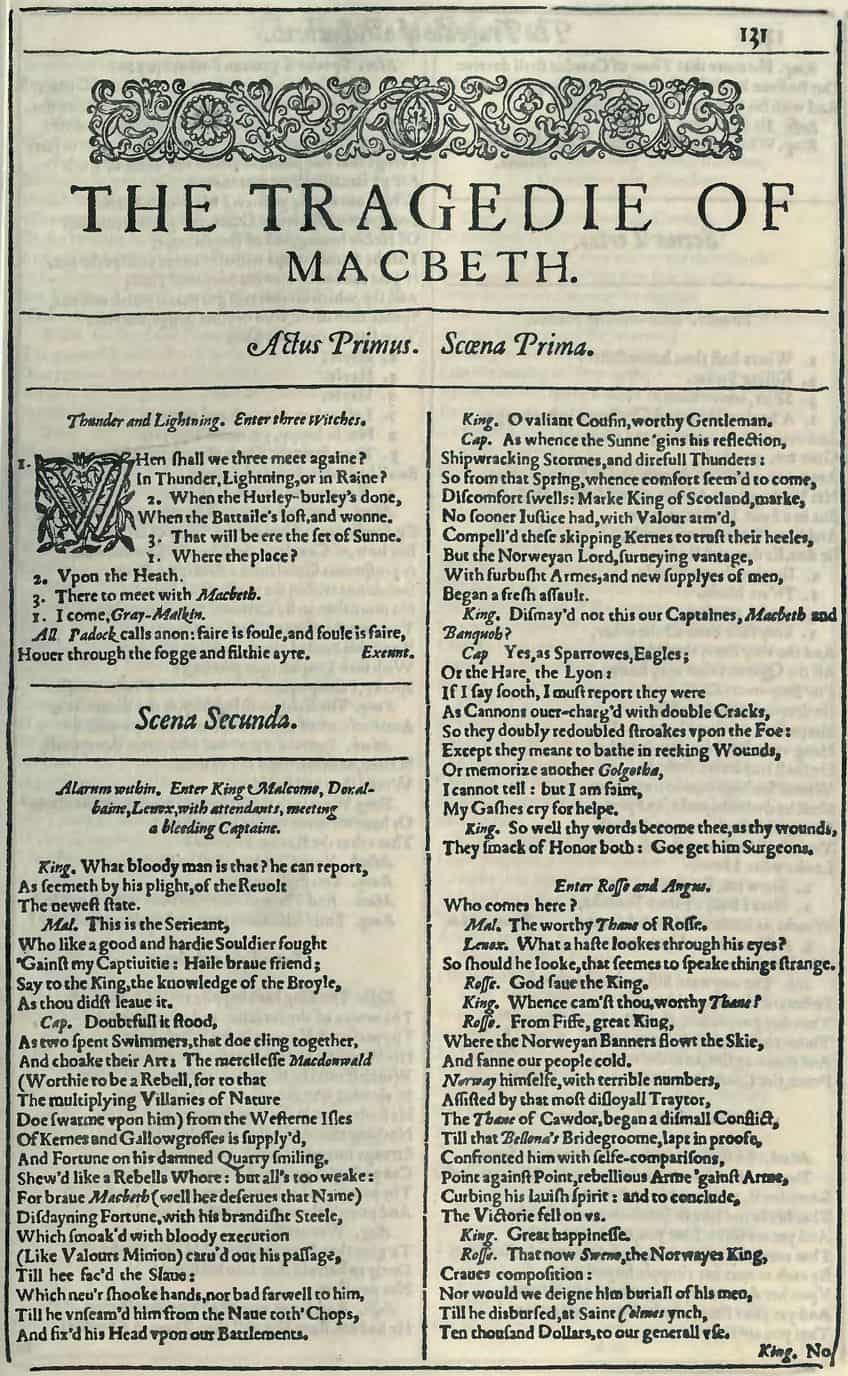

Trochee

This metrical foot also consists of two syllables, the first being accented while the second syllable is not. For example, the word morning, with the accented syllable being underlined. An example can be taken from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606) from Act IV scene I. Each line has four trochees and is therefore a trochaic tetrameter.

“Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn, and caldron bubble.”

Spondee

A spondee consists of two syllables and both of them are accented, unlike the trochee and the iamb. This type of metrical foot is often used by poets to shift the poem’s rhythm. For example, the word birthday, with both accented syllables being underlined. Spondees can also be two words with emphasized single syllables right next to each other.

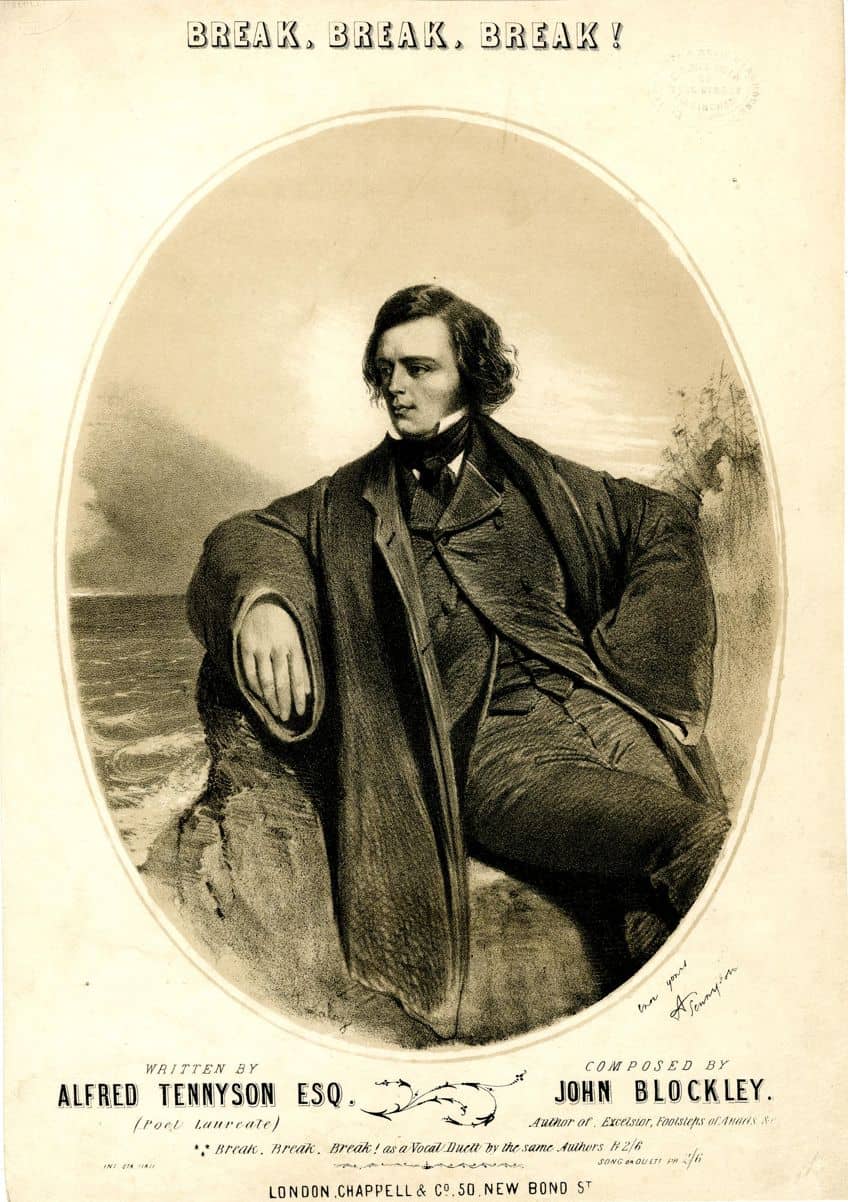

For example, go go! The following lines are an example of spondee being used in Lord Tennyson’s (1809-1892) poem, Break, break, break (1842).

“Break, break, break,

On thy cold gray stones, O Sea!”

Another way to create rhythm in poetry is through line breaks or by even leaving silent spaces. Another popular way of creating rhythm is through repetition. This technique highlights the phrases or single words that are being repeated. In Maya Angelo’s (1928-2014) poem, Still I Rise (1978), she repeats, “I rise” and increases the frequency of this phrase as she moves through the poem. The poem starts with, “I’ll rise” and towards the end, the phrase changes to, “I rise” which is also repeated to emphasize her confidence and strength.

“You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

’Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.”

Rhyme in Poetry

What often comes to mind when we think of poetry is how they sometimes rhyme. In order for a poem to rhyme, words are chosen that have similar pronunciations, such as: kind, blind, find, rind, for example. However, rhyming is not as important as it used to be and poems do not need to rhyme for them to be classified as poetry. Traditional forms of poetry rely on a rhyming scheme, like sonnets, rimes royal, villanelles, and so on. The three types of rhymes are:

- Perfect rhymes: These are pairs of words that sound identical but with a small difference. For example, “power” and “shower” or “can’t” and “shan’t”.

- Slant rhymes: Also known as a half-rhyme, these are pairs of words that are similar in sound but their last vowels are pronounced differently, so they sound almost the same but they do not rhyme completely because they are pronounced slightly differently. For example, “crate” and “braid” or “swarm” and “worm”.

- Homophones: These words are spelled differently from one another but sound the same. For example, “tide” and “tied”.

William Shakespeare (c.1564 – 1616) used rhyme in his poem, Sonnet 55: Not marble nor the gilded monuments (1609) with the last word of every second line, following the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

“Not marble nor the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme,

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone besmeared with sluttish time.

When wasteful war shall statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword nor war’s quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory.

’Gainst death and all-oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth; your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

So, till the Judgement that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes.”

Format and Form in Poetry

The structure of a poem is what forms it and determines whether the poem is a villanelle, a sonnet, a slam poem, a ghazal, free verse, a contrapuntal, or something completely different and new. Form can refer to the breaks in a poem, such as line and stanza breaks. Poets decide when one line ends and a new line begins, which words start and end each line, and this helps to emphasize the sounds and images that they find important and want the reader to recognize. There is a lot more freedom in poetry and therefore, poetry does not follow the same formatting as prose. There may be empty spaces between the lines, or single words may hold a line on their own. Some sentences may end in strange places, or be arranged in a way that the poem even forms a visual picture.

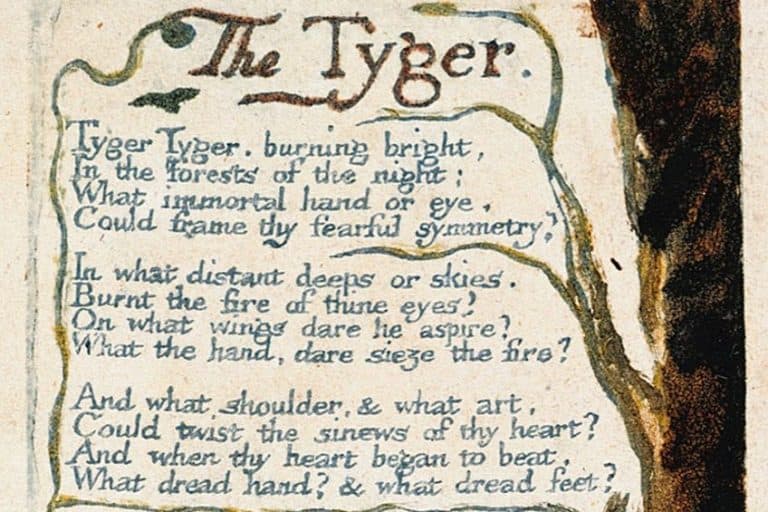

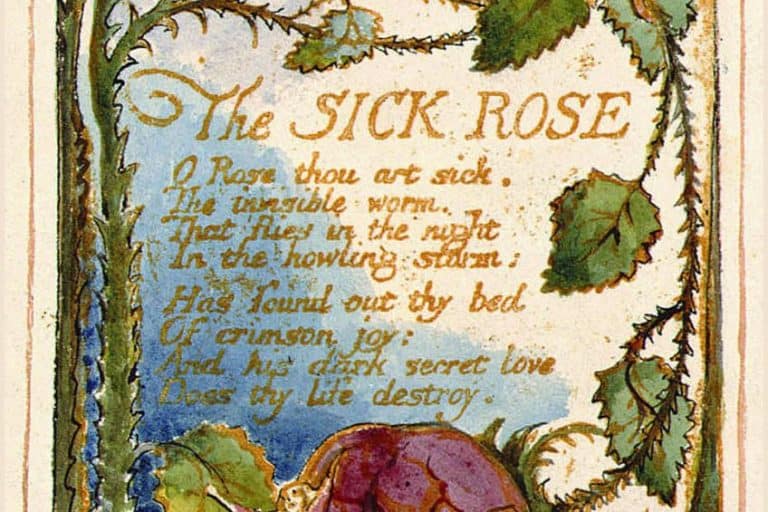

Literary Devices in Poetry

Literary devices help the poet to express complex thoughts and ideas through language. Most poems use literary devices and the ones that are commonly used when writing poetry are: Metaphors, similes, figurative language, puns, onomatopoeia, personification, and juxtaposition. A famous example of a poem that uses various literary devices is [You Fit Into Me] (1971) by Margaret Atwood (1939-present). She uses a simile in the first stanza that, at first, presents a pleasing image of a hook that fits neatly into an eye closure (a metal loop).

The juxtaposition in the next stanza is quite jarring with an image of an eyeball being pierced by a hook.

“you fit into me

like a hook into an eye

a fish hook

an open eye”

How To Write a Poem: Step-by-Step

If you have not written a poem before, you may be a little bit nervous about how to write a poem. Writing a poem does not have to be daunting. It can actually be fun and even a form of creative release. We have listed some poem writing tips below to help you on your writing journey so that you will know how to write poetry.

Step 1: Think of a Topic – What Is Your Poem About?

It is easier to write a poem once you have a topic in mind – that spark of an idea that sets the writing in motion. However, picking a topic is not always easy. Below are some ideas of where you could find inspiration for writing your poem.

Finding Inspiration in Other Literary Works

As much as we would like to think so, nothing in this world is absolutely unique. Many of us become writers because we have been inspired and influenced by other writers, and the same goes for topics. Perhaps you have a few favorite poems that have inspired you to look into writing poetry yourself – hence you reading this article.

For example, “We Real Cool” (1959) by Gwendolyn Brooks (1917 – 2000) inspired Terrance Hayes (1971 – Present) to write the poem, “The Golden Shovel” (2010).

Your Own Life

We each have our own story to tell, and so do you. Many poets have written about their own life experiences: Love, loss, heartbreak, family, friendships, and so on. These are common themes, but your experience is different from the next person. In Piscilla Lee’s (1966 – Present) poem, Family Dinner (2000), she describes her experience at a family dinner during the holiday season.

Nature

Nature has inspired many artists, designers, and poets in history and today. There is so much beauty and many lessons to be learned by looking at nature. In The World Is Too Much With Us (1807) by William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850), the poet criticizes the modern world for distancing ourselves from nature.

Everyday Things

Poetry is not just about the big things in life, but can also be about finding beauty in the mundane, everyday things. For example, Angel Nafis (1988 – Present) celebrates the daily habit of moisturizing in her poem, Ode to Shea Butter ([s.a]).

Events That Happened or Are Happening in the World

Many poets have used real-world events as inspiration for their poetry, capturing these events through a personal lens – this is how we get different perspectives from various people on the same topic. The Young and Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak (1941) by Archibald MacLeish (1892 – 1982) speaks about the dead soldiers in World War II.

There is power in poetry to share experiences and convey ideas on how to impact and change the world around us.

Step 2: Write Down Your Ideas – Generating Material

This can take the form of journaling, or simply writing random sentences or words that come to mind regarding the topic you have chosen that you could later use in the poem. You do not need to worry about turning it into a poem at this point – just write and see what falls onto the page. Let the creative juices flow. Every poet has their own way of brainstorming, some may start by writing their ideas down as a prose poem to later add breaks, and so on.

Step 3: Choose a Form for Your Poem

In this step, you will choose the form and style that you would like your poem to be. At this point, you may have a lot of ideas or material that you can now shape and finesse. You can choose from many forms of poetry. Whichever form you choose, you will want it to enhance the content of the poem. Below are a few brief examples of poetic forms:

Sonnet

William Shakespeare often used this form of poem which consists of 14 lines. You can make use of any formal rhyme scheme when writing a sonnet, using 10 syllables in each line in most cases if writing in English.

Below is an example of Shakespeare’s most famous poem, Sonnet 18: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day (1609).

“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

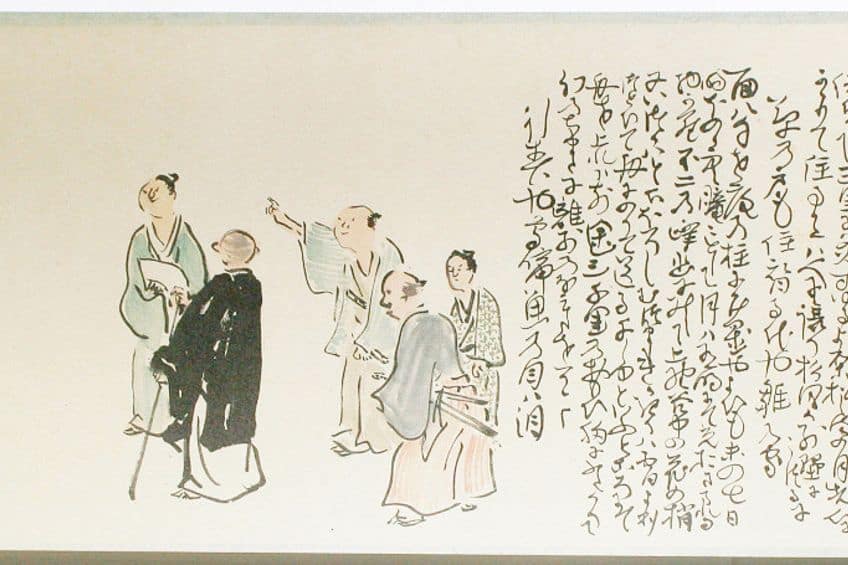

Haiku

A Haiku is a short poem originating from Japan that consists of three lines. There are always five syllables in the first line and third line, while there are seven syllables in the second or middle line. The below example is by Matsuo Bashō (1644 – 1694), entitled The Old Pond (1686).

“An old silent pond

A frog jumps into the pond—

Splash! Silence again.”

Limerick

A Limerick poem consists of five lines and follows the strict rhyme scheme of AABBA in which the first two and fifth lines rhyme, while the third and fourth lines have a different rhyme. Although this poem form can often be rude or humorous in subject matter, it does not have to be. The following is an example of a limerick poem entitled,

There was an Old Man on the Border (1872) by Edward Lear (1812 – 1888).

“There was an old man on the Border,

Who lived in the utmost disorder;

He danced with the cat, and made tea in his hat,

Which vexed all the folks on the Border.”

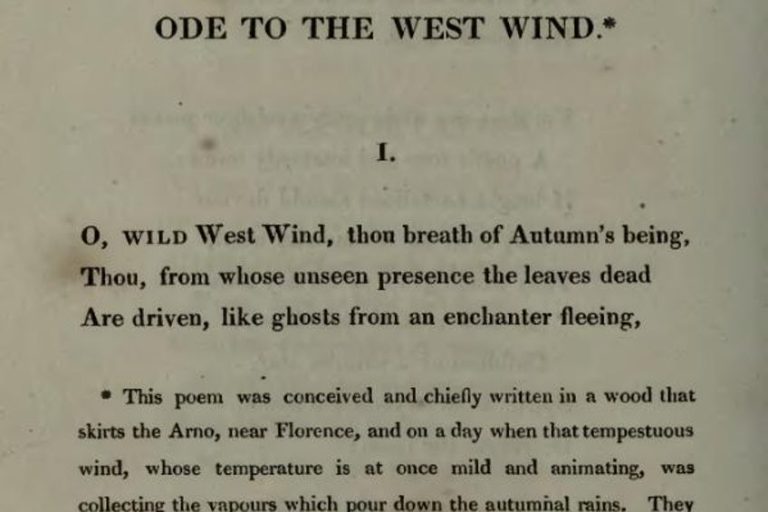

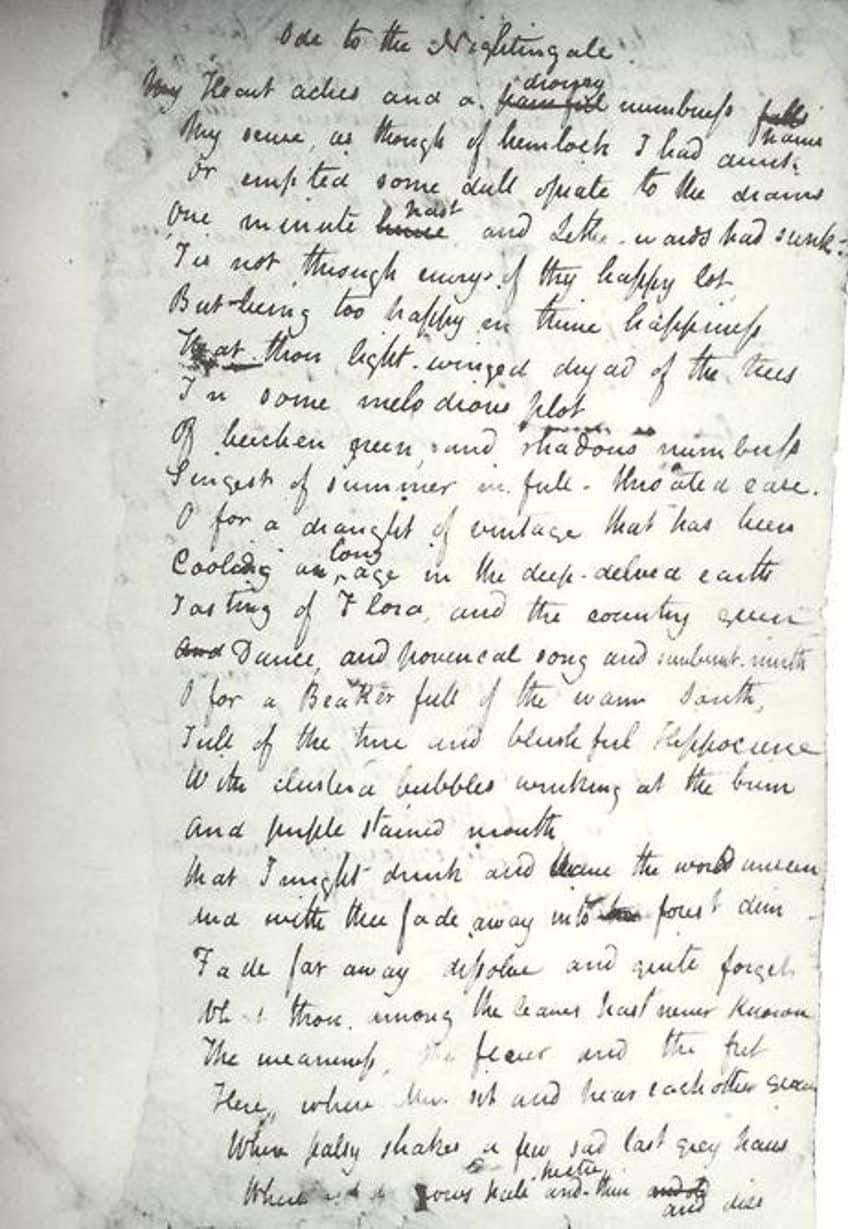

Ode

An ode is a lyric poem that is a dedication celebrating a person, a subject, an object, or event and uses vivid descriptive language. Classically, this form of poem is traditionally set to music and is meant to be sung. Its stanzas vary and its meter is irregular. John Keats’ (1795 – 1821) Ode to a Nightingale (1819) is an example of an ode. It is a lengthy poem, thus we have provided the first stanza below.

“My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

‘Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.”

Free-Verse

You may choose not to use a standard form at all and simply write your poem as free-verse. Most modern writers are drawn to this form of poetry writing. But even if you are choosing a free-verse, your poem will need structure and style. Are you going to be using any recurring structures for the stanzas or the lines or even punctuation? How can your unique form be used to enhance what is within the poem?

It may help to read poems that are written in the form that you would like to use, so that you have a reference point and template to follow.

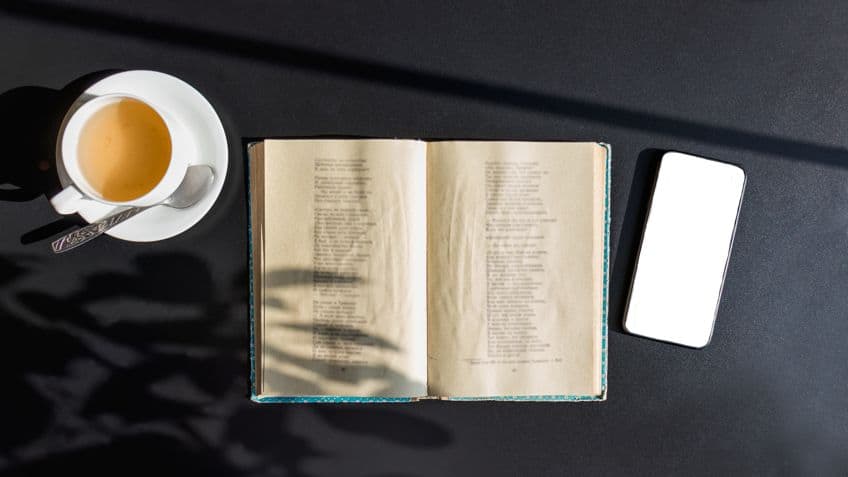

Step 4: Do Research – Read Poetry

You may find it difficult to write a specific type of poem if you have not read poetry in the form that you have chosen. So, if you have never written a sonnet before, it would be very helpful to read a couple of them first. It will give you a lot of ideas of how you can use that form for your own poem.

Step 5: Write the First Draft

Now that you have chosen a topic, gathered some material, and have done some research, it is now time to start writing your poem. It is important to write for yourself. It can put a lot of pressure on you if you think about all those eyes that may read your poem. For now, just think about yourself and how you would like the poem to read. Worrying about whether other people will like it or understand it can make for an anxious writing process. You may even uncover things that you would like to change or an entirely new angle that you would like the poem to go while you are writing.

Do not be afraid to switch up your plan, poetry is fluid.

Step 6: Read Your Poem Out Loud

As we know, rhythm is very important in poetry and one of the best ways to find out the rhythm of your poem is to read it out loud. You can then fine-tune it, perhaps by strengthening your line breaks where you feel there should be a pause. You may even want to change the position of some of the words, or replace ones that seem awkward which may only stand out when reading out loud.

Step 7: Take a Break

It can be easy to get well acquainted with a poem that you are working on, reading it over and over again until you cannot see it clearly anymore. It is a good idea to let the poem rest for a bit, for some it is a few days to a week. You can decide how long a break you need.

The aim is to come back to your piece with fresh eyes and continue to fine-tune things such as word choice, structure, and line breaks.

Step 8: Revise Your Poem

Once you have taken a break and let your poem rest, it is time to revise it. You may need to have an open mind during this process and have some patience, as your poem may change quite a lot. That is completely okay and may even be helpful for the piece. Changing the poem may open you up to new ideas and ways of structuring the poem. Because a poem is so short in comparison to other forms of writing, it is important to remove anything that is irrelevant or that is not contributing to the core thread of the poem. Conciseness is key, and every word and every line of the poem should contribute something crucial.

And that is it for our poem writing tips! We hope that you enjoyed reading this guide on writing poetry for beginners. After you have completed your first poem, we hope that you continue to explore the world of poetry. It is a beautiful thing to be able to put emotion and thoughts onto a page, and what better way than by writing a poem!

Frequently Asked Questions

Does a Poem Need To Rhyme?

The first answer is no, your poem does not need to rhyme for it to be a good poem. The second answer is that it depends on what type of poem you are writing. Traditional forms of poetry rely on a rhyming scheme, like sonnets, rimes royal, villanelles and so on.

How Long Should a Poem Be?

When writing a poem for yourself, your poem can be as long as you like. However, when writing a poem for potential publishing, you should try and limit the length of your poem to one page. Editors of literary journals or magazines want each issue to contain as many writers as possible, and thus they will most likely go for the shorter poem when faced with choosing between two good ones. In addition to this, you want your poem to keep the reader engaged. A poem that is extremely lengthy may be difficult to follow all the way through for some readers.

What Makes a Poem a Good Poem?

What makes a poem impactful and memorable are essentially the words used to create the poem. Not only that, but how you have used them. Words that are well placed, that create an impact with sound or imagery, are what stir emotions within the reader. At the same time, everyone has different tastes when it comes to poetry, the same way that people have different tastes in music. If one person does not like your poem, it does not mean that others will not like it.

Jaycene-Fay Ravenscroft is a writer, poet, and creative living in South Africa with over 6 years of experience working in a contemporary art gallery. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Ancient History at the University of South Africa, with additional subjects in Archaeology and Anthropology.

With a passion for learning, Jaycene-Fay is very much inspired by symbology and the connection between everything in this world. Trained to analyze and ‘critique’ art, she is passionate about exploring the meaning behind each artwork she encounters and understanding how it connects to the artist’s cultural, historical, and social background. Writing is Jaycene-Fay’s way of having a finger in every pie: to research, share knowledge, and express herself creatively.

Learn more about Jaycene-Fay Ravenscroft and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Jaycene-Fay, Ravenscroft, “How To Write a Poem – A Detailed Guide to Writing Poetry.” Art in Context. March 27, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/how-to-write-a-poem/

Ravenscroft, J. (2023, 27 March). How To Write a Poem – A Detailed Guide to Writing Poetry. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/how-to-write-a-poem/

Ravenscroft, Jaycene-Fay. “How To Write a Poem – A Detailed Guide to Writing Poetry.” Art in Context, March 27, 2023. https://artincontext.org/how-to-write-a-poem/.